Listening Practice

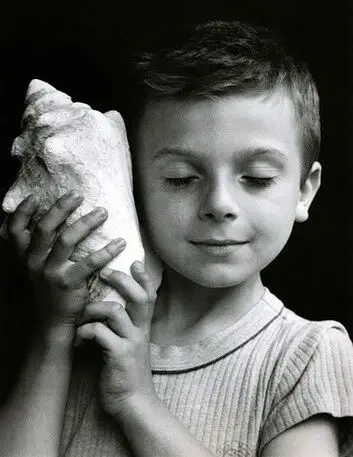

A Tilt of the Ear

We listen to the world around us every day.

Why do we need to listen differently?

BeSpeak

Listening habits change over time as the sound environment changes. And sound environments are changing profoundly. Some soundscapes, the sounds that form them, have disappeared while others are endangered, and all are changing in some way or another.

No one can embody the listening habits of the past or of indigenous cultures or of other species — although there are resonant crossovers.

I can listen to artifacts from diverse sound cultures or glean past soundscapes from literature or partake in a different listening culture through tourism, music or film — but a lifetime of being inside the soundscape I inhabit shapes my listening, especially in terms of the meaning and biases I give sounds in soundscapes.

So, if environments are collapsing, soundscapes are also threatened.

How then is listening affected?

Optimistic

Sound is rarely a closed system and is inherently changeable, which is a place of optimism.

The complexity of everyday sounds at play are expressive of relationships and convergences between diverse people, environments, cultures, and ways of being that carry significant layers of information and potentials for understanding the other.

Listening relationships constitute in location – dislocation known-unknown, immersion-distraction, adherence-disconcertion.

Not as binaries but as moments of coming to know difference dynamically.

Embodied

Being profoundly embodied, listening starts with a location in the body: breath, heartbeat, nervous system, mind chatter, and body tempo.

Then, the embodied experience moves out into the world and encounters itself relationally through sound.

Whereas visual culture focuses on horizons, acoustic culture is in constant movement and constant coalescence as sounds flow around and through the matter encountered, including our bodies — and their inherent embodied orchestras.

The way bodies locate themselves, their place in their locale, things in approach and retreat, and the way bodies discern other bodies in proximity.

The soundscape is mostly invisible and taken for granted.

Receptive

Listening implies self-directed attention distinct from hearing, which is how sound interacts with the ears’ mechanisms.

In listening, there is attention to being-in-the-world that seeks connection. This implies that being-as-listening holds the possibility of coming to understand existence with openness and generosity.

Without models of receptiveness, awareness also collapses.

Biases

Experiences of sound and the meanings derived are as diverse as the listeners imbedded in their own culture and habituation of listening.

Generally, listeners favor sound experiences that calm or excite the nervous system and bring pleasure. This is not a given but rather a bias often based in the sound traditions and values of different cultures. What soothes in one tradition may excite in another.

We shape and are shaped by our environments.

In Western European culture, the shape and meaning of sounds are tethered to philosophical movements, such as the Enlightenment’s glorification of the pastoral that influenced structures of music, for example. What is considered idyllic and calming today traces back to those ideas.

So,much of what is deemed natural is actually learned response.

Habits

Listening rests and breaks sound habituation through alternatively merging attention to specificity in sound.

If you grew up next to a railway track, the roar of passing trains may be pleasurable. Similarly, if you grew up next to highway, the monotony of tires punctuated by large transport trucks may act as a lullaby. If you grew up in a machine shop, the whirl and grind of machines may make you feel at home, and if you grew up in a monastery, quietude puts you at ease.

If you grew up in a monastery and now live next to a highway, you are probably in trouble — at least for a little while.

This argument has its limitations as there are types and levels of sounds that are psychologically numbing or physically damaging regardless.

The point is that understanding one’s habituation and working from inside and outside of that space, as in all things, brings awareness and connection with other states of being.

The awareness gained amplifies listening potency and then, one day, you realize it has snowballed, and the world and people in it as well as your own self have changed.

You are more receptive, sensitivities are amplified, a gentle generosity has entered your day. You are listening.

At least, this is how it happened to me.

Audio Activism

Why is this of consequence for audio producers?

As we move deeper into audio culture defined by podcasts, producers can discern and make choices about the listening practices they are cultivating.

Listening is a lost art like so much of what it means to be alive in this time of collapse with profound loss of all kinds, including acoustic diversity.

If we are to have a viable future, listening to each other and creature existence as well as understanding the attendant suffering and trauma, those who work with audio for the public have a role to play. Audio producers are now in a place of influencing listening attenuation.

Podcasts have the potential for that reach.

You, Producer-Listener

Which leads me back to you, audio maven.

What kind of a listener are you?

How do you listen to what another person is saying beyond and including their words into an expansive present?

Are you sensitized to your own internal and external soundscapes to the extent that it shapes creative and technical audio applications?

Do you raise the potency of your acoustic genre through listening awareness?

How do you move through and making meaning of the sounds you inhabit?

There is listening and then there is listening.

© 2024 Andrea Dancer

Sources

2014 Andrea Dancer, Profound Listening, UBC Doctoral Dissertation